By Sam Whyte

Since the first page of the first minutes of the first presbytery meeting in America held in the First Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia is missing, it is noteworthy perhaps that the extant records begin with an interrupted sentence “…which being approved of and sustained,” and a floating pronoun, “his ordination took place on the next Lords day, December 29, 1706.” The page also includes a Latin phrase,” De regimene ecclesial” or “by the direction of the church,” an apt description of the early years of the Presbytery of Philadelphia.

The attendees at that first meeting in March of 1706 were pastors and licentiates, seven of them, by name Francis Makemie, John Hampton, George Macnish (sometimes McNish), John Wilson, Samuel Davis, Nathaniel Taylor and Jedediah Andrews. Taking into consideration the backgrounds of these men, their affiliations and influences, the presbytery was an early American melting pot of Scottish, Scotch-Irish, English, Dutch, Hugenot and Welsh. Only Mr. Andrews had been born in the colonies, in Higham, Mass. He was a 1795 graduate of Harvard College and a Congregationalist at heart.

The attendees at that first meeting in March of 1706 were pastors and licentiates, seven of them, by name Francis Makemie, John Hampton, George Macnish (sometimes McNish), John Wilson, Samuel Davis, Nathaniel Taylor and Jedediah Andrews. Taking into consideration the backgrounds of these men, their affiliations and influences, the presbytery was an early American melting pot of Scottish, Scotch-Irish, English, Dutch, Hugenot and Welsh. Only Mr. Andrews had been born in the colonies, in Higham, Mass. He was a 1795 graduate of Harvard College and a Congregationalist at heart.

The Rev. Mr. Francis Makemie (1658-1708), Irish-born, Scottish-educated, came to America about 1690 as an itinerant missionary and traveled in Maryland, Virginia, the Carolinas and even Barbadoes not only proclaiming the Gospel but also being involved in commercial ventures. His interest in forming the presbytery was in part “to correct the most proper measure for advancing religion and propagating Christianity in desolate places,” i.e., parts of the Middle Colonies. Too, he wanted the clergy to be able to give support and help to one another. Other than the theological influences of the Heidelberg Confession, the Westminster Confession of Faith and the Larger and Shorter Catechisms of 1647, “by the direction of the church,” no formal constitution was drawn up.

With the exception of Jedediah Andrews, the other five founders were known as “the Makemie boys.” They came from churches in Maryland that Makemie is credited with starting up: Rehoboth (sometimes Rehobeth), Snow Hill, Manokin and Wicomico (combined) and Upper Marlborough. Two Delaware churches, Lewes and New Castle, were also in the presbytery.

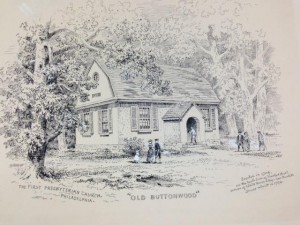

From the beginning, the body was not known as The Presbytery of Philadelphia; it was the presbytery, The Presbytery, the General Presbytery, and its initial meeting took place in the very tiny First Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, organized in 1698, the congregation whose pastor was Mr. Andrews. With his roots in New England Congregationalism, however, he and some of his followers were cautious of organizing. “We will accept the name of Presbytery provided the body… shall assume no authority over the churches. We do not care for the name, but we do care for the freedom of the churches.” (E[zra] H[all] Gillette. “History of the Presbyterian Church.” Congregational Quarterly. Vol. 1, October 1877, 24).

“De regimene ecclesial” found in those early minutes may apply generally to the larger church and the years ahead for the presbytery, but specifically the phrase refers to the essay required of John Boyd at his ordination held on that December day in Scots Church, Freehold, NJ, the second meeting of the presbytery, the only one held outside of Philadelphia. Boyd has the distinction of being the first Presbyterian pastor to be ordained in America.

Along with Makemie, Boyd made the first overture ever at an American presbytery: “First, That every minister in their respective congregations, read and comment upon a chapter of the Bible every Lord’s Day, as discretion and circumstances of time, place, etc. will admit.” The agenda for early meetings of the body included exhorting ministers to engage in personal Bible study, overseeing ordinations and getting ministers “settled,” adjudicating arguments, admonishing ministers for their delinquencies, and even ordering the people of Snow Hill to show their “faithfulness and care” in collecting the tobacco promised their minister, Mr. Hampton. (Minutes of the Presbytery, May 19, 1708).

Makemie and Boyd died weeks apart in the summer of 1708. Eight years later, on Sept. 21, 1716, the presbytery with which both were associated was officially named The Presbytery of Philadelphia when three presbyteries — Philadelphia, New Castle and Long Island — formed the Synod of Philadelphia. A fourth, Snow Hill, was considered but never constituted. “It having pleased Divine Providence so to increase our number, as that, after much deliberation, we judge it may be more serviceable to the interest of religion to divide ourselves into subordinate meetings or Presbyteries, constituting one annually as a Synod.” (David Turley, American Religion: Literary Sources and Documents. Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis, 1998, 373).

Historian and theologian, the Rev. Dr. Thomas Murphy, pastor for almost half a century at the Frankford Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, notes the significant influence of The Presbytery of Philadelphia in such events as the 1725 founding of the Log College; the 1729 Adopting Act; the 1739 visit of Whitefield; the 1741 Old and New Light Schism; and the 1858 healing of the Schism. (The Presbytery of the Log College; or The Cradle of the Presbyterian Church. Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publications and Sabbath School Work, 1889, 58).

Noteworthy also is the Presbytery’s involvement in the organization of the Synod, the first General Assembly, its initial gathering held in Philadelphia First in 1789 and for 54 subsequent years except for three; the Board of Missions (later the Board of Home Missions); the influx of Presbyterian immigrants into Philadelphia, particularly 100 Irish from Belfast in 1736. And “by the direction of the church,” the true spiritual legacy of The Presbytery of Philadelphia, shines with the men and women, clergy and lay, who labored so valiantly in the early years; founded churches, colleges, universities and seminaries; wrote hundreds of scholarly and popular books; composed anthems and hymns, provided leadership outside the church in the stirrings of democracy; and tirelessly heralded the Gospel of Jesus Christ in a promising new land.